We’re just about a week away from the start of the 2019 season. With the new defense from Keith Patterson and having seen very little of it at Tech so far, I wanted to preview it a little before game 1.

How it works

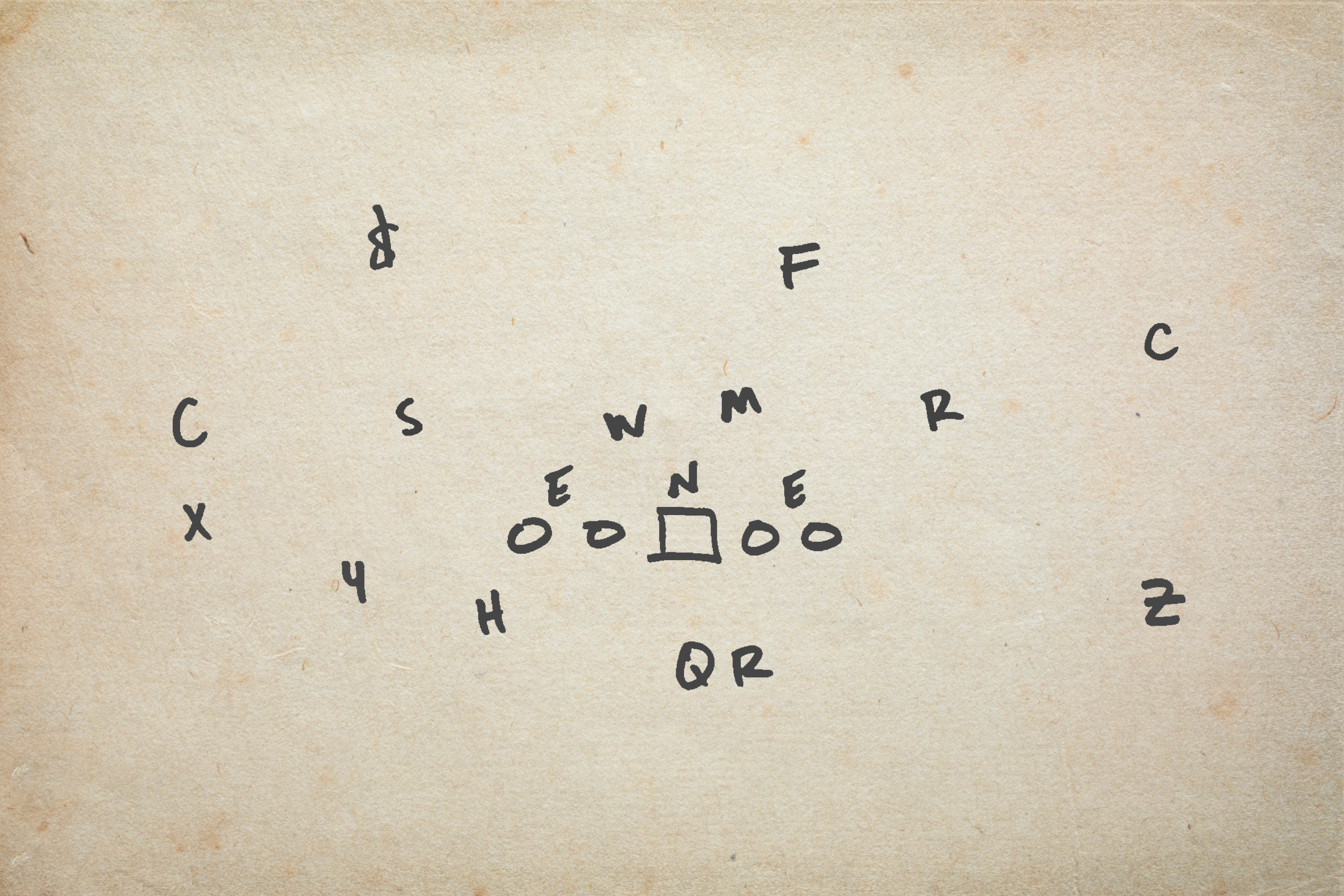

Both Texas and Iowa State have employed this base front defense the last few seasons, as well as Georgia and LSU. The guys over at Match Quarters have done a great job of breaking this defense down. Reminders: the defensive alignment is referred to 404 (defensive ends are aligned inside the tackles (in the 4 space/gap) and the defensive tackle/nose is aligned over the center (in the 0 space/gap); the front is also referred to as “tite.”

Strengths

The Tite Front works because it forces the offense to bounce everything outside. The two DEs (4is) in the B gaps close off the main gaps for spread teams, the “conflict” gaps. Spread offenses attack the B gap because that is where the conflicted player usually is for a defense. By closing both B gaps, the offense has to either run in the A gap (where the defense has 3 players to cover 2 gaps) or run it outside. Defenses that base out of the Tite Front don’t mind the bounce because their LBs can now chase down the RB while its outside players (Raider & Spur) box everything back inside.

The 404 alignment does several things for the box:

- The offensive line can’t climb because of the 4is, and

- It frees up at least one of the inside linebackers

And this from Ian Boyd with Football Study Hall:

The major goal of the 4-0-4 “tite” front with it’s double 4i-technique “defensive ends” is to use the DL primarily as a tool for clogging the interior while leaning on the LBs and secondary to handle the rest of the field.

With the DEs sitting in position to handle the B-gaps, the defense then has three guys positioned between the tackles to handle the two remaining A-gaps [nose tackle and two middle/inside linebackers]. The nose will typically lock one down while one LB will be able to take the other while the other is freed up to key the ball or take on an insert block. What’s more, not only is the defense well positioned to defend all the gaps between the tackles but two of the five guys up front are off the line and thus “moving targets” for the offense to try and block.

The positioning of the linebackers and of the DEs makes life very difficult for offenses trying to execute spread run game favorites.

And then there’s this (and much more) from Brady Grayvold of USAFootball.com

Offenses have evolved to the point that quarterbacks are reading defenders to see their next move. If they don’t step up, the quarterback hands the ball off. If they leave their designated pass drop, the quarterback throws the hot route right behind them. What the Tite front does is allows your defenders to not in be in conflict when they are in the core of the formation. Because you are gapped out with four defenders on the interior, your fifth player is a free hitter and your sixth man in coverage has edge run responsibilities but can play the pass first by alignment.

TL;DR: This defense clogs up the inside running lanes, forces the ball outside to your faster defenders, and reduces conflicts in read situations.

Another strength of this defense is its ability to change the structure of the defense without changing the scheme. This is helped by utilizing hybrid players and can be achieved by moving one or two players – the Raider and Spur.

Weakness

Now, some of the weaknesses of this defensive scheme is that the 404 front by itself is bad at creating a pass rush. Patterson, confirmed through many player interviews, addresses this by creating an extensive blitz package. You’ll see that Raider rush in from the outside, one or both inside backers blitz up the middle, or any combination of defensive backs coming in from the outside. Your season sack leader will not be from any in the defensive line group.

Another weakness can be getting control of forcing the runs outside. The interior alignment is designed to push things outside and let your faster defenders control the space in the flats. If these defenders take bad angles, or can’t tackle reliably in space, forcing the run outside doesn’t help much. Having said that, you will still be more likely to have defensive help outside from other defensive backs, or forcing the runner even wider out towards the sideline – forcing the runner out wide should allow for more defenders to converge on the ball.

Both Texas and Iowa State were successful in defending the run in the Dime sub package of this defense – putting 6 DBs on the field and having them stop the run along the perimeter. Tech would be able to do this by subbing one of the DEs off the field for another CB, and moving the Raider LB onto the line of scrimmage as an outside pass rush.

The challenge of the tite front is that the “overhang” defenders in those OLB positions have to be ready to show hard on the edge because there’s no one in the C-gap unless they or an ILB get there fast and hard. If there’s a defender in one of those spots that struggles to play the edge with a good dose of physicality than the offense can leverage that spot and widen the front.

Boyd and others note that defending read option type plays can be difficult in this front, but an adjustment and strength of this defense is the ability to show one front and move post snap into a different front. This muddies the waters for offensive players trying to read a player who, after being identified as the read player presnap, has moved.

Texas and Iowa State have found success in running this style of defense against Big 12 competition: ISU and UT went 1-2 in rush defense, ISU was 1st in scoring defense (UT was 4), ISU was 2nd in pass defense, ISU and UT were 2nd and 3rd in total defense, ISU and UT were 2nd and 3rd in red zone defense, and ISU and UT were 3rd and 4th in pass defense efficiency.